By Jeff James

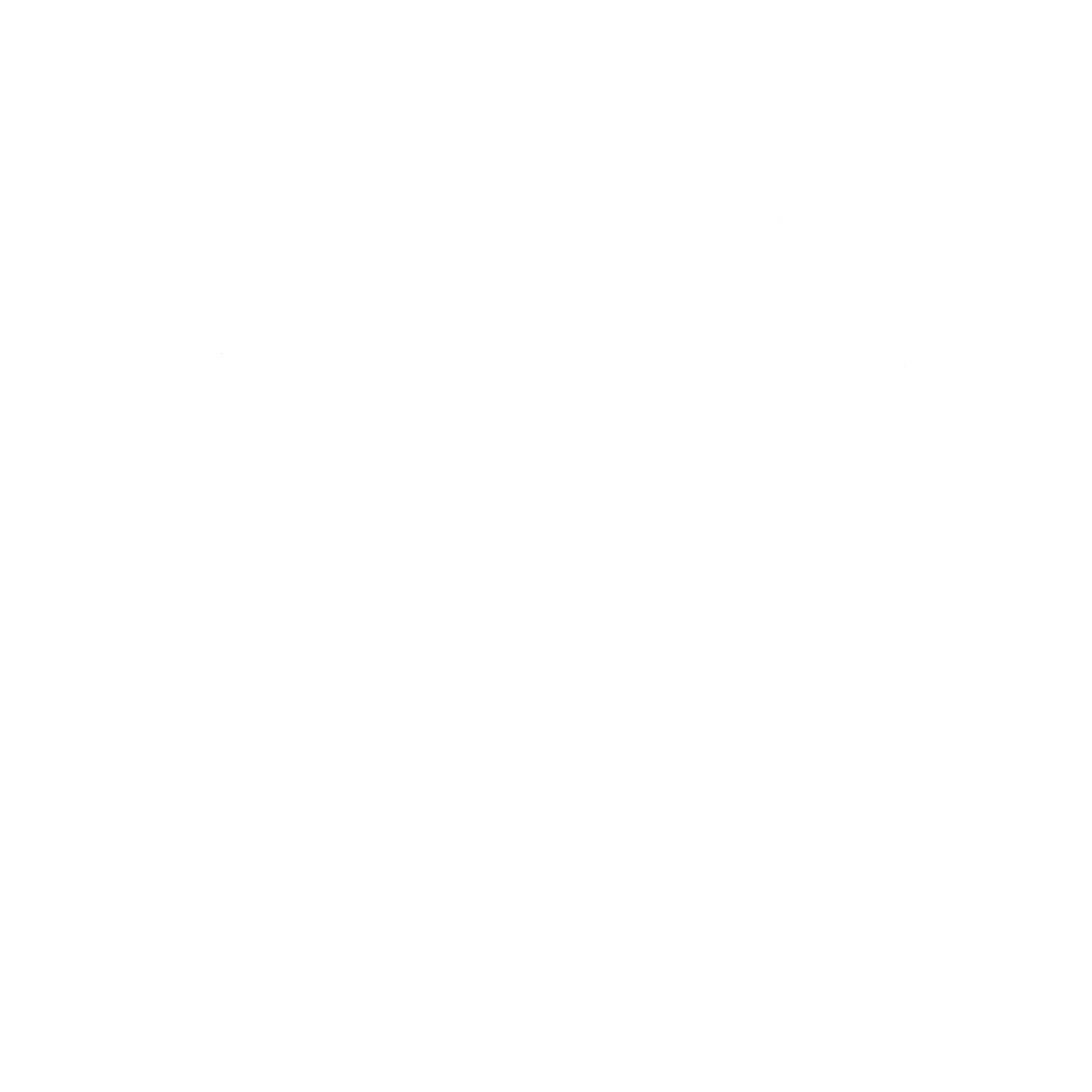

When I saw the tears fall in great drops upon the table, creating craters of dust and dark marks on the stained wood, I knew I had asked the wrong question. I wanted to know if she remembered the day her father walked her from her home in the lowlands of southwestern Ethiopia to the highland rainforests of Chiri, and then left her there, alone. Forever.

She remembered, and her tears told the whole story. There were no further details necessary. Posy’s life, all 9 years of it, has been a tragic series of abandonment.

Posy was born to the nomadic, warrior tribe of the Menit people, pastoralists roaming the lower Omo river valley. Around the age of 5 or 6 Posy suffered her first epileptic seizure. As a result, her siblings were no longer allowed to play with her, and she was forced to sleep outside. Her parents were concerned that a curse may have been put upon their family.

The frequency of her seizures increased, and her parents determined there must be evil at work. I’ve heard horror stories of epileptics thrown into rivers to drown or be devoured by crocodiles, or tied to a tree and left to die. But Posy’s family had compassion for her and chose to leave her in a bustling town with a fistful of money (about $5), a hundred of miles from her home, and among people whose language she didn’t speak. She was 7 years old then, and by the grace of God, that town was Chiri.

Her money lasted but a few days and the nights were cold and scary. But one afternoon, while Posy was begging in the street, mercy showed her face. Posy met a woman who took pity on her and offered a job fetching water and cleaning. In exchange for service, Posy received one meal a day and a corner inside to sleep. But then another seizure gripped her, terrifying the woman.

The woman was convinced that what she witnessed was nothing short of evil, and evil was not welcome in her home. And so Posy returned to the streets to beg.

Eventually Posy met a nurse who understood epilepsy, and who offered her servant work in exchange for food, but not shelter. She could sleep in the yard or in the cow shed. But Posy’s seizures continued and one day, while cooking over an open fire, she convulsed and toppled right into it. She couldn’t extract herself until the tremors ended, and by then, her burns were severe. The nurse cleaned and dressed her wounds as best she could and sent her to rest under a shade tree. After a few days, however, her wounds became terribly infected and the smell of burned flesh irritated the nurse. It was an intolerable odor. And so, yet again, Posy was sent away with nothing but the shredded clothes that clung to her body, and a fever that shook her to the core.

She was found by a Lalmba employee, lying in a ditch, confused, and close to death. She was admitted into our hospital where her burns were treated, she was cleaned and given high doses of antibiotics. But the damage was bad, really bad, and surgery was needed to restore use of her arm. The infection needed advanced care that we couldn’t provide. We took her to the Missionaries of Charity in Addis Ababa, truly a place where saints flock to cure and comfort the sick and dying. It was her best hope of surviving, and after 4 months of surgery and recovery, she healed perfectly. She’s badly scarred, but she is strong and able-bodied. The sisters sent her back to Chiri, a town where she had no home, no family, and only one friend, Lalmba.

A home she found in Lalmba’s orphanage, and at the age of 9, she will begin the 1st grade in just a couple of weeks. She has a bed inside a house with windows and doors and a roof that doesn’t leak, and on her bed she has Tweety Bird sheets. She wakes up to breakfast and a routine that values education and hard work, and accepts her for who she is. And yet, I know, when she closes her eyes at night, she imagines her next step, when all this goodness is over and the bed once again is the street. She can’t possibly believe the horrors are gone; life can’t be that good. But it is, by the grace of God, it is. Posy, through a tragic path, a perilous route, found safety and shelter in a home that will never expel her, one that will nourish her with love and acceptance. It’s too soon for her to believe it’s real; but I looked into her tear-filled eyes, and I held her scarred hand, and I promised her, this home, this family of orphans and castoffs, is just like her, and like them, she will never be sent away.

That is a promise I intend to keep.

Understanding Poverty

By Hillary James

The students in Dr. Colleen Fenno’s freshman writing class at Concordia University in Wisconsin haven’t thought much about world poverty before. Colleen, a Lalmba supporter, partners with Lalmba each semester to give her students a first-hand education in what it means to be one of the millions living in extreme poverty. Each semester Hillary skypes with the students to tell them about Lalmba’s work in Africa. Colleen then asks her students to perform one task in solidarity—either washing their clothes by hand for 2 days, carrying 10 pounds on their head for 1 mile, or eating only rice and beans for 48 hours—-then write about it. Below are some of the comments from her students after their experience:

“Although I already knew I was fortunate just to live in the United States, this walk further imprinted in my mind just how lucky I am. Unlike those in developing countries I wasn’t walking for my survival, but instead for a college class. I am not only fortunate enough not to have to walk to get my water, but I also am able to attend college. This is more than most people would even dream of in a developing country.”

“So, I picked out the clothes I wore from Friday and Saturday and brought it back up with me to wash by hand. As I walked back up to the bathroom on my floor I stopped in my room to grab dish soap. I scrubbed my clothes and rung out the soap. Afterwards, I walked back to my room and decided to hang my clothes by the window to dry. Later that night, I flipped them over so the other side could dry. It took me a while to wash what I wore from the past two days, and I got water all over myself. Doing this challenge helped me realize I should not take simple things, like washer and dryer machines, laundry detergent (Tide pods), and fabric softener, for granted.

“So, I picked out the clothes I wore from Friday and Saturday and brought it back up with me to wash by hand. As I walked back up to the bathroom on my floor I stopped in my room to grab dish soap. I scrubbed my clothes and rung out the soap. Afterwards, I walked back to my room and decided to hang my clothes by the window to dry. Later that night, I flipped them over so the other side could dry. It took me a while to wash what I wore from the past two days, and I got water all over myself. Doing this challenge helped me realize I should not take simple things, like washer and dryer machines, laundry detergent (Tide pods), and fabric softener, for granted.

Before completing this challenge, I complained about having to walk down two flights of stairs just to get to the laundry room.

Now I know that I am lucky that I am able and fortunate enough to walk those stairs and throw my clothes in a machine that will clean my clothes for me. Manually washing clothes and having to find a spot to place them to dry was not simple. “Living below the line” helped me realize so many things I take for granted, and I am glad that I was challenged with this experience.“

A New Partner in Health

By Hillary James

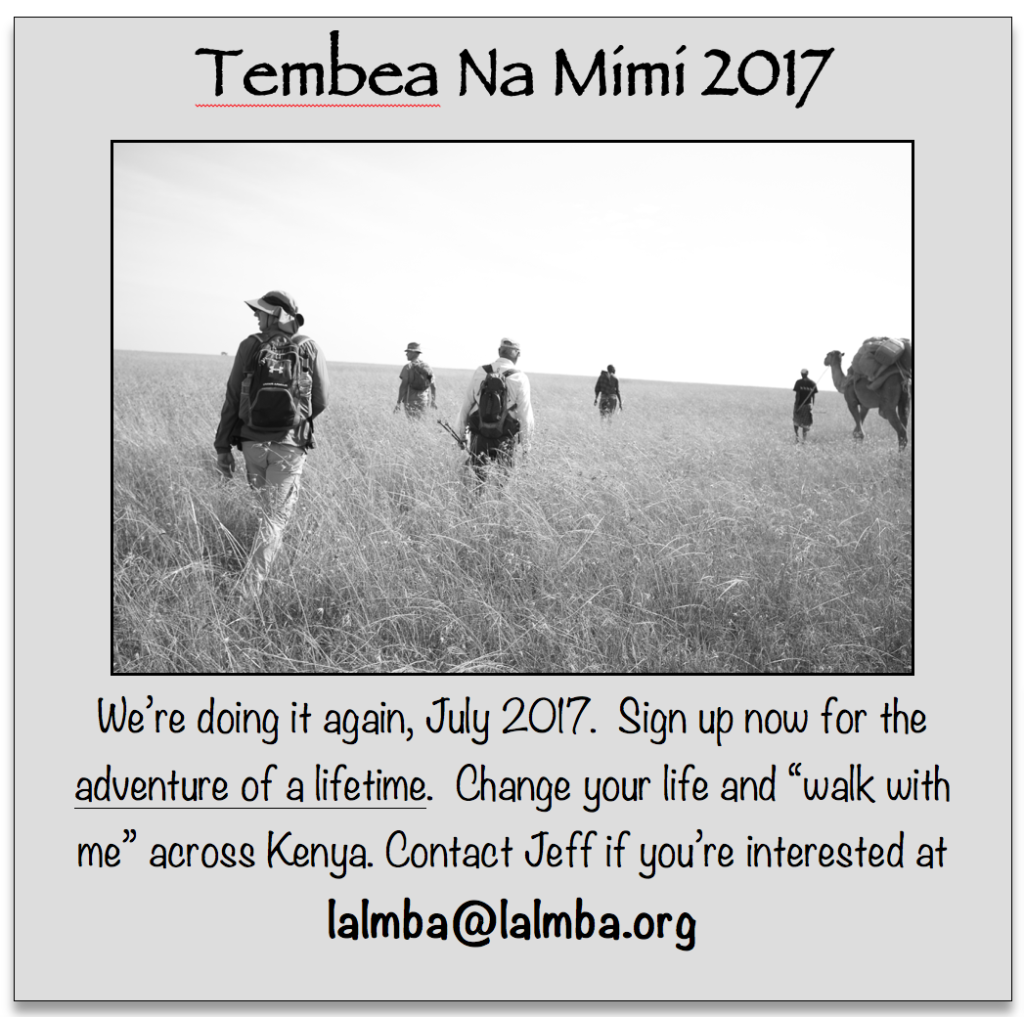

It is hard for us to fathom the hardship for the sick in Ethiopia to reach adequate medical care. Agaro Bushi, a tiny village 4 hours’ walk from Lalmba’s health center, is a place without electricity, water, or an adequate road to reach the outside world. A health clinic there was started by Ruth Brogini, the wife of the former Swiss ambassador to Ethiopia and the director of an organization called SAED (www.saedetiopia.org). Since its inception, the clinic has been a first stop for the sick. If the illness is significant, the patient must travel the 4 hours by mule to reach Lalmba’s Chiri Health Center. There are several river crossings, one with a single log acting as a bridge, and harrowing hills with steep slopes.

Ruth has been struggling to keep the clinic open, challenged by her inability to manage from Switzerland. Last year, Lalmba partnered with Ruth to provide the oversight for the clinic with weekly visits from Lalmba’s volunteers in Chiri, while SAED provides the funding, and a new ambulance for Lalmba’s use. When the road is too bad for a vehicle, we strap medicines and equipment onto mules’ backs to carry them to Agaro Bushi.

The last time I visited Agaro Bushi, a woman 34 weeks pregnant came to the clinic saying she had not felt her baby move for some days. Susan Botarelli, our expat public health director, realized the baby had died and the woman would require a transfer to a hospital. The woman’s husband arranged for a mule, and he and his brother walked alongside the patient up and down mud-slick roads, across precarious creek crossings, 4 hours until we reached Lalmba’s vehicle. The woman stoically lay down in the back of the Land Cruiser for the bumpy ride to Chiri, knowing all along that her almost full-term baby was most certainly dead. Her husband stroked her face, whispering reassurances as they spent the day trying to reach medical care. I will always remember her strength in the face of despair, and her stoicism in the arduous journey to reach our clinic. Without Lalmba’s involvement, Ruth had considered closing the clinic, given its remoteness and the difficulties in managing it. Lalmba’s expertise in managing rural African health clinics now has a new opportunity to provide good primary health care to a very needy population! We are so pleased to have a new partner in doing what we do best, being a source of health for those in the world who need it most.

Left to Right: Atinafu (Chiri Health Center Assistant Manager), Jeff, Romeo (Lalmba’s Ethiopia Project Director), Tafesse (CHC General Manager), and Ruth Brogini (Director of SAED) in front of the new ambulance.

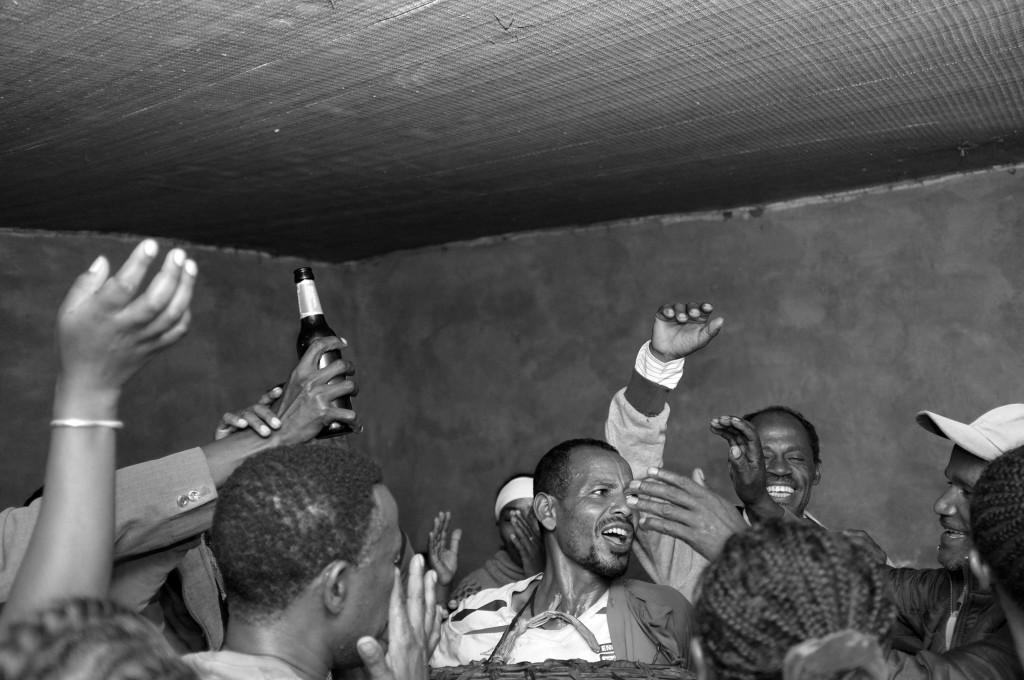

Picture This:

Sights from our African Journeys